Not Much Happens Here Why Can t Crossing Over Happen Again Bio

How is the same procedure responsible for genetic recombination and diversity also the cause of aneuploidy? Understanding the steps of meiosis is essential to learning how errors occur.

Organisms that reproduce sexually are thought to take an reward over organisms that reproduce asexually, because novel combinations of genes are possible in each generation. Furthermore, with few exceptions, each individual in a population of sexually reproducing organisms has a distinct genetic composition. Nosotros accept meiosis to thank for this variety.

Meiosis, from the Greek give-and-take meioun, significant "to make small," refers to the specialized procedure by which germ cells divide to produce gametes. Because the chromosome number of a species remains the same from i generation to the adjacent, the chromosome number of germ cells must be reduced by one-half during meiosis. To reach this feat, meiosis, unlike mitosis, involves a single round of DNA replication followed by two rounds of cell division (Figure 1). Meiosis also differs from mitosis in that it involves a process known as recombination, during which chromosomes exchange segments with 1 another. Every bit a consequence, the gametes produced during meiosis are genetically unique.

Researchers' initial agreement of meiosis was based upon careful observations of chromosome behavior using lite microscopes. And so, in the 1950s, electron microscopy provided scientists with a glimpse of the intricate structures formed when chromosomes recombine. More than recently, researchers have been able to identify some of the molecular players in meiosis from biochemical analyses of meiotic chromosomes and from genetic studies of meiosis-specific mutants.

Meiosis Is a Highly Regulated Process

Meiosis represents a survival machinery for some simple eukaryotes such every bit yeast. When conditions are favorable, yeast reproduce asexually by mitosis. When nutrients get limited, however, yeast enter meiosis. The commitment to meiosis enhances the probability that the next generation volition survive, because genetic recombination during meiosis generates four reproductive spores per cell, each of which has a novel genotype. The entry of yeast into meiosis is a highly regulated process that involves significant changes in gene transcription (Lopez-Maury et al., 2008). By analyzing yeast mutants that are unable to complete the diverse events of meiosis, investigators accept been able to identify some of the molecules involved in this complex procedure. These controls have been strongly conserved during evolution, so such yeast experiments have provided valuable insight into meiosis in multicellular organisms as well.

In most multicellular organisms, meiosis is restricted to germ cells that are fix aside in early development. The germ cells reside in specialized environments provided past the gonads, or sex activity organs. Inside the gonads, the germ cells proliferate by mitosis until they receive the right signals to enter meiosis.

In mammals, the timing of meiosis differs profoundly between males and females (Figure 2). Male germ cells, or spermatogonia, practise not enter meiosis until after puberty. Even and so, only limited numbers of spermatogonia enter meiosis at whatever i fourth dimension, such that adult males retain a pool of actively dividing spermatogonia that acts as a stem cell population. On the other manus, meiosis occurs with quite different kinetics in mammalian females. Female person germ cells, or oogonia, stop dividing and enter meiosis inside the fetal ovary. Those germ cells that enter meiosis become oocytes, the source of future eggs. Consequently, females are born with a finite number of oocytes arrested in the first meiotic prophase. Within the ovary, these oocytes grow within follicle structures containing large numbers of back up cells. The oocytes will reenter meiosis only when they are ovulated in response to hormones. Human females, for case, are born with hundreds of thousands of oocytes that remain arrested in the first meiotic prophase for decades. Over time, the quality of the oocytes may deteriorate; indeed, researchers know that many oocytes die and disappear from ovaries in a procedure known as atresia.

Meiosis Consists of a Reduction Segmentation and an Equational Division

Ii divisions, meiosis I and meiosis II, are required to produce gametes (Figure iii). Meiosis I is a unique cell sectionalization that occurs only in germ cells; meiosis 2 is similar to a mitotic division. Before germ cells enter meiosis, they are more often than not diploid, meaning that they have two homologous copies of each chromosome. Then, just before a germ cell enters meiosis, it duplicates its Deoxyribonucleic acid so that the jail cell contains four DNA copies distributed between ii pairs of homologous chromosomes.

Meiosis I

Compared to mitosis, which tin have identify in a matter of minutes, meiosis is a slow procedure, largely considering of the fourth dimension that the cell spends in prophase I. During prophase I, the pairs of homologous chromosomes come up together to class a tetrad or bivalent, which contains 4 chromatids. Recombination can occur between any two chromatids inside this tetrad structure. (The recombination process is discussed in greater detail afterward in this article.) Crossovers between homologous chromatids can be visualized in structures known as chiasmata, which appear belatedly in prophase I (Figure 4). Chiasmata are essential for accurate meioses. In fact, cells that fail to form chiasmata may not be able to segregate their chromosomes properly during anaphase, thereby producing aneuploid gametes with abnormal numbers of chromosomes (Hassold & Hunt, 2001).

At the finish of prometaphase I, meiotic cells enter metaphase I. Hither, in sharp contrast to mitosis, pairs of homologous chromosomes line up contrary each other on the metaphase plate, with the kinetochores on sister chromatids facing the same pole. Pairs of sex chromosomes also marshal on the metaphase plate. In human being males, the Y chromosome pairs and crosses over with the Ten chromosome. These crossovers are possible because the 10 and Y chromosomes have small regions of similarity well-nigh their tips. Crossover between these homologous regions ensures that the sexual activity chromosomes will segregate properly when the prison cell divides.

Side by side, during anaphase I, the pairs of homologous chromosomes carve up to unlike daughter cells. Before the pairs tin separate, nonetheless, the crossovers between chromosomes must be resolved and meiosis-specific cohesins must exist released from the arms of the sister chromatids. Failure to separate the pairs of chromosomes to dissimilar daughter cells is referred to every bit nondisjunction, and it is a major source of aneuploidy. Overall, aneuploidy appears to be a relatively frequent event in humans. In fact, the frequency of aneuploidy in humans has been estimated to exist as high as ten% to 30%, and this frequency increases sharply with maternal age (Hassold & Hunt, 2001).

Meiosis II

Following meiosis I, the daughter cells enter meiosis II without passing through interphase or replicating their Dna. Meiosis II resembles a mitotic sectionalization, except that the chromosome number has been reduced by half. Thus, the products of meiosis Ii are four haploid cells that contain a single copy of each chromosome.

In mammals, the number of viable gametes obtained from meiosis differs between males and females. In males, four haploid spermatids of similar size are produced from each spermatogonium. In females, however, the cytoplasmic divisions that occur during meiosis are very asymmetric. Fully grown oocytes within the ovary are already much larger than sperm, and the time to come egg retains well-nigh of this volume as information technology passes through meiosis. As a issue, simply one functional oocyte is obtained from each female meiosis (Figure 2). The other 3 haploid cells are pinched off from the oocyte as polar bodies that contain very little cytoplasm.

Recombination Occurs During the Prolonged Prophase of Meiosis I

Prophase I is the longest and arguably most of import segment of meiosis, considering recombination occurs during this interval. For many years, cytologists have divided prophase I into multiple segments, based upon the appearance of the meiotic chromosomes. Thus, these scientists have described a leptotene (from the Greek for "thin threads") phase, which is followed sequentially by the zygotene (from the Greek for "paired threads"), pachytene (from the Greek for "thick threads"), and diplotene (from the Greek for "ii threads") phases. In contempo years, cytology and genetics have come together so that researchers now understand some of the molecular events responsible for the stunning rearrangements of chromatin observed during these phases.

Recall that prophase I begins with the alignment of homologous chromosome pairs. Historically, alignment has been a difficult problem to approach experimentally, but new techniques for visualizing individual chromosomes with fluorescent probes are providing insights into the process. Recent experiments suggest that chromosomes from some species take specific sequences that act as pairing centers for alignment. In some cases, alignment appears to begin every bit early as interphase, when homologous chromosomes occupy the aforementioned territory inside the interphase nucleus (Figure 5). However, in other species, including yeast and humans, chromosomes exercise non pair with each other until double-stranded breaks (DSBs) appear in the DNA (Gerton & Hawley, 2005). The formation of DSBs is catalyzed by highly conserved proteins with topoisomerase activity that resemble the Spo11 protein from yeast. Genetic studies accept shown that Spo11 activity is essential for meiosis in yeast, because spo11 mutants fail to sporulate.

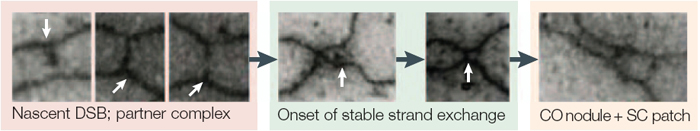

Following the DSBs, one DNA strand is trimmed back, leaving a 3′-overhang that "invades" a homologous sequence on some other chromatid. As the invading strand is extended, a remarkable construction called synaptonemal complex (SC) develops around the paired homologues and holds them in close annals, or synapsis. The stability of the SC increases every bit the invading strand get-go extends into the homologue and then is recaptured by the broken chromatid, forming double Holliday junctions. Investigators have been able to observe the process of SC formation with electron microscopy in meiocytes from the Allium plant (Figure half dozen). Bridges approximately 400 nanometers long begin to form between the paired homologues following the DSB. Only a fraction of these bridges volition mature into SC; moreover, non all Holliday junctions volition mature into crossover sites. Recombination will thus occur at but a few sites along each chromosome, and the products of the crossover will go visible as chiasmata in diplotene after the SC has disappeared (Zickler & Kleckner, 1999).

Figure six: Visualization of chromosomal bridges in Allium fistulosum and Allium cepa (plant) meiocytes.

The sites of double-stranded break (DSB) dependent homologue interaction can be seen as approximately 400 nm bridges between chromosome axes. These bridges, which probably contain a DSB that is already engaged in a nascent interaction with its partner Deoxyribonucleic acid, occur in large numbers. Their formation depends on the RecA (recombination protein) homologues that are expressed in this species. In the next phase of homologue interaction, these nascent interactions are converted to stable strand-invasion events. This nucleates the germination of the synaptonemal complex (SC).

© 2005 Nature Publishing Group Gerton, J. L. & Hawley, R. South. Homologous chromosome interactions in meiosis: diversity amidst conservation. Nature Reviews Genetics 6, 481 (2005). All rights reserved. ![]()

References and Recommended Reading

Gerton, J. L., & Hawley, R. S. Homologous chromosome interactions in meiosis: Diversity amidst conservation. Nature Reviews Genetics half dozen, 477–487 (2005) doi:10.1038/nrg1614 (link to article)

Hassold, T., & Chase, P. To err (meiotically) is human being: The genesis of man aneuploidy. Nature Reviews Genetics 2, 280–291 (2001) doi:10.1038/35066065 (link to article)

Lopez-Maury, L., Marguerat, S., & Bahler, J. Tuning gene expression to changing environments: From rapid responses to evolutionary adaptation. Nature Reviews Genetics ix, 583–593 (2008) doi:ten.1038/nrg2398 (link to article)

Marston, A. L., & Amon, A. Meiosis: Cell-cycle controls shuffle and bargain. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 5, 993–1008 (2004) doi:10.1038/nrm1526 (link to article)

Page, S. L., & Hawley, R. S. Chromosome choreography: The meiotic ballet. Science 301, 785–789 (2003)

Petes, T. D. Meiotic recombination hot spots and common cold spots. Nature Reviews Genetics 2, 360–369 (2001) doi:10.1038/35072078 (link to article)

Zickler, D., & Kleckner, North. Meiotic chromosomes: Integrating construction and function. Annual Review of Genetics 33, 603–754 (1999)

Source: http://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/meiosis-genetic-recombination-and-sexual-reproduction-210

0 Response to "Not Much Happens Here Why Can t Crossing Over Happen Again Bio"

Post a Comment